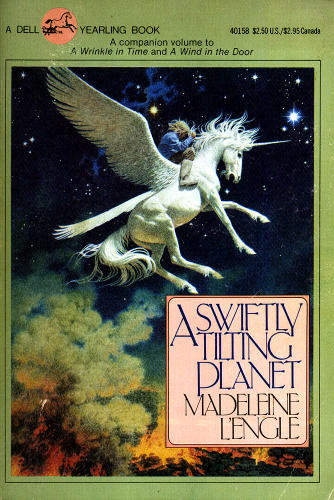

I have been thinking recently about war. The children of my generation, our parents... their childhoods were dominated by the ever-looming threat of nuclear war. I am reading Madeline L'Engle's book, A Swiftly Tilting Planet, and its opening pages are rife with this fear. The fear of utter annihilation, of complete destruction, of the death of the human race. "One madman can push a button and it will destroy civilization." I began rereading this book this evening because it is about how a few people might tip the balance, might make some small difference in the world in favor of life, in favor of love and creation, in favor of harmony. The book, written in the late '70s, plays with time and narrative in a mind-bending way. The past is not past, and "as long as the future hasn't happened, there's a chance it may not happen." I began rereading this book tonight because I need reassurance, sometimes, I need to believe in the possibility of goodness. The possibility of peace.

I have been thinking recently about war. The children of my generation, our parents... their childhoods were dominated by the ever-looming threat of nuclear war. I am reading Madeline L'Engle's book, A Swiftly Tilting Planet, and its opening pages are rife with this fear. The fear of utter annihilation, of complete destruction, of the death of the human race. "One madman can push a button and it will destroy civilization." I began rereading this book this evening because it is about how a few people might tip the balance, might make some small difference in the world in favor of life, in favor of love and creation, in favor of harmony. The book, written in the late '70s, plays with time and narrative in a mind-bending way. The past is not past, and "as long as the future hasn't happened, there's a chance it may not happen." I began rereading this book tonight because I need reassurance, sometimes, I need to believe in the possibility of goodness. The possibility of peace.But the world is a very different place now.

Once upon a time, this country used nuclear weapons as a deterrent--at least in theory. Once its citizens feared nuclear war as the very real and very close end days of the human race. Now, we have been living for two generations with the fact that we are the only country in the history of the world to have actually used a nuclear weapon against a civilian population. There were no consequences for us, safe on this side of the ocean, and American citizens have begun to forget the devastation, the sickening and useless destruction that war can cause. When we feel threatened, the average Joe cries out, "Nuke 'em till they glow and them shoot 'em in the dark!" We continue to build our arsenal, and the itch to use it, to show it off, is ever-present and worsening.

We mourn the "massacre" of thirty people in a senseless killing spree perpetuated by a single, deranged individual--and yet in not a few countries across the world, that many people and more die every day, from violence, from starvation, from disease. We rant on about the barbarity of suicide bombers and ponder, peripherally mystified out of the corner of our eyes, what could drive them to such heinous acts. What we really cannot grasp is how they can involve themselves so personally in the killing of innocents, how they can violate the fundamental sense of self as a member of the human community, how they can confront their own violence so directly. It is not the killing of innocents we cannot bare, but this warped selfhood that destroys itself by destroying its community. We kill innocents, but we do so mechanically, in a sanitary manner. We make vague political threats and formulate theoretical dreams of a time when "war is peace," and a bomb falls thousands of miles away. We cannot hear it. We do not see it. We are, as individuals, uninvolved. We are clean, we are innocent. We are isolated. We are the living dead who have forgotten death. We have become the madmen who press the buttons, without thought to the consequences.

I talk with people my age, and sometimes I am astounded by what we say. At work the other day, a customer was celebrating her 86th birthday with her close friends. "I hope I never live that long," said one of my coworkers. "Really!?" I asked, amazed. "You would rather die sooner than later? You don't want to live to see your grandchildren, and maybe even your great-grandchildren? You don't want to grow old with the people you love?" My coworker shrugged and said, "I just don't want to get senile." Something within me ached... The senility of youth, to want to always be young! To never want to deepen, to age, to slow down... Is there so little we love about this place, that we would rather die quickly once we have used it up, used ourselves up? We are the living dead, who have forgotten life and so have forgotten that death, too, is life. Life transformed. Life changed. We bring death to others and we wish it on ourselves, but we do not understand it. We wish death to be mere oblivion--in war, so that the dead we make cannot reproach us; and in ourselves, so that we might not lose ourselves to the flux of time.

We wish it secretly and fervently, but wishing cannot make it true.

I do not know how to talk sense into the madness we take these days for reason. I do not know how to restrain the hand that rests steadily on the button. It is not my hand. It is the invisible hand of the market, it is the hand of the "selfish gene," it is the suicidal hand of a culture that has lost sight of the value of living in its diseased and obsessive pursuit of unlimited life.

But it is not my hand.

I am amazed and saddened by the co-worker who didn't want to live to be eighty-six. I've known many people who were alive and vital into their eighties; in the year she died, my grandmother was still going weekly to a neighborhood nursing home to play bingo with other seniors who weren't as healthy and active as she was.

ReplyDeleteI've had a lot of people around me die recently, and at forty-one, I'm wrestling with issues of wanting to live another forty years, or more, and realizing that no, I don't want to live forever.

It shocked me as well. But what was more shocking was that, when I began asking others, every single one of them said the same thing.

ReplyDeleteMy best friend recently lost his cousin, who had only just turned thirty. So this has been on my mind recently. I don't want to live forever, but I want to grow old. The older I get, the more I realize that there are projects I want to pursue and things I want to accomplish that take time, and I welcome that time and that process of maturing and aging.

I guess that's a whole other issue. It's hard to imagine devoting your whole life to something when everywhere around us are examples of how a lifetime of work can be wiped out in an instant, if an angry child or a power-hungry political leader decides to act rashly.

"Every knowledge starts with reason and ends in faith."

ReplyDeleteWe must have faith in HIS Administration.

Best wishes.

Surjit,

ReplyDeleteI'm not sure I agree. If anything, I'm inclined towards the Socratic opinion that knowledge begins with faith and then develops through the processes of reason (eventually transcending it and integrating the rational and nonrational). But that is an obscure and tangential philosophical point.

The real point is that I don't believe there is a "He" somewhere who will just step in and make things right if we just wait long enough and pray hard enough into the silent Void. We are the Divine manifest, just as a bird or a tree or a sunset, too, manifests an aspect of the Holy. "We must be the change we wish to see in the world." - Gandhi

I do have faith. But my faith is in humanity--that humanity will, someday, grow to see itself as it truly is: sacred, and intimately interconnected with the sacred world.

Another pertinent quote, this time by Ani DiFranco: "God's work isn't done by God, it's done by people."

ReplyDeleteLater in that same song is my favorite line: "She's trying to sing just enough so that the air around her moves, and make music like mercy, that gives what it is and has nothing to prove."

May my love, and even my mourning, be this kind of music, which gives of itself entirely, which creates movement and change, and which needs no justification or external reference point like some imagined Old Man in the sky.

A good quote..God's work isn't done by God,it done by people...

ReplyDeleteNow suppose a mad man pushes THAT button..whose work will it be God's or.....

My best wishes.

You have some very deep thoughts here. I just browsed over here through mybloglog.

ReplyDeleteIn front of my house lives an elderly couple who run a convenience store. The funny thing is that they take forever to actually get stuff done, whether it be cleaning or handing me a bag of Doritos, they take a really long time to move around because they're so old! BUT, they keep their mind and body occupied everyday, hence one of the reasons they're still capable of carrying conversations with folks. Deep down inside they are patiently living out their final days.

ReplyDeleteI sincerely hope to live as long as possible, given that there just isn't enough time in the world to do everything one wishes. However, I consider to die giving my life for someone else really noble. It might be better to die bravely like that while doing something noble, than to patiently wait death out. If I could choose my way to go, I would choose option 1. I mean it sure beats the regular heart attack, or the "died in their sleep," bit. Just what I think. :)

Thanks, don thieme. :) It's nice to know those blog databases really do help. ;)

ReplyDeleteWelcome!, that's very true. :) Actually, I was just about to post an excerpt from a letter I wrote to a friend about that very idea: I am quite willing to suffer, and even die, in order to be true to the principle of love that guides my life.

ReplyDeleteOn the other hand, the simple act of dying for another does not render that act noble or loving. There are soldiers who die in war "for our country," but I cannot say that I think their deaths have truly helped to make the world a better place (think how their families could have been saved their mourning, or how perhaps they could have worked to cure diseases or create beautiful and inspiring art, or any of the infinite other things that could truly improve the quality of life in the world--if they had lived, instead of dying in war). And think of people like Gandhi and MLK, who made such a huge difference because of how they lived and how they were willing to die for their love, though they were not willing to kill for it.

Sometimes it is just as important, and perhaps harder, to live for the sake of love--especially when it does not earn you honor or recognition, when the effects of love are more subtle and harder to gauge. Then it takes real commitment to stay true to that principle.

That might be true as well. But consider the types of deaths that occur around the world. In any country, soldiers die, and even if it means that the world isn't a better place, I would hate to think that their deaths are meaningless. What would happen if there weren't soldiers willing to give their life for your country? Who would take their place? Unfortunately, not everyone is meant to create beautiful art, or be a scientist that cures diseases. All types of people are needed in the current world that we live in.

ReplyDeleteI'm not from the US. In Colombia, there's a war against a terrorists organization known as the FARC. Where would Colombia be if it weren't for the military fighting against them? Not in a pretty good state. The FARC provides almost all of the cocaine that goes into the US, if soldiers weren't here giving their lives trying to stop it, then who would take their place? I'm not saying that I don't agree with you, MLK did amazing things. But he was assasinated, and his death will always be remembered to many.

Welcome!, unfortunately, I don't know much about the situation in Columbia right now, but I can understand when there are times when a soldier's death is noble and has meaning, especially when that person is dying to protect civilians or resist occupiers or tyrants (though, as you said, the world needs all kinds of diverse people, and that includes strict pacifists like myself who, while compassionate towards those who fight, would never willingly choose violence).

ReplyDeleteI think it becomes more complicated, though, when powerful countries themselves become occupiers and tyrants--is it all right to claim that a soldier's death is noble, simply because his government put him in a kill-or-be-killed situation? In that kind of situation, the soldier's job is not to die for his country, but to kill for his country, and his death is just an unfortunate risk.

To me, the nobility of dying for others comes from the choice to live according to a principle of love and peace, even if others choose to react to that choice with violence. This is why the assassinations of MLK and Gandhi were so powerful--because they chose to live bravely by their belief in nonviolence, even though they knew it could provoke violence against them. We remember their deaths because they are examples of the tragic and useless destruction of loving individuals, so that even their deaths reinforce their own commitment to nonviolence and help to stop the cycle of destruction rather than to drive it on out of fear or revenge. But how can I believe that the deaths of U.S. soldiers in Iraq, for instance, has some principled meaning, when it has become so evident that the war itself was unjust and unnecessary? Perhaps the Iraqi civilians who struggle to survive on a daily basis and rebuild a devastated region might die nobly in the crossfire. But death that results from one's own choice to use force or involve oneself in violence voluntarily, and which is likely only to perpetuate that violence, I just cannot consider noble. I do not think it is noble to be a pawn of power.