New York: Berg Publishers Ltd, 2009.

Review by Alison Shaffer

After the flight to Charlotte, North Carolina, two days earlier, I had learned one thing for certain: I was not a natural flyer. My first time in an airplane in more than fifteen years had left me feeling queazy and disoriented, retreating to the quiet sanctuary of my hotel room for the evening as I attempted to ground myself in a new landscape and a new city hundreds of miles from my home in chilly, hilly western Pennsylvania. High-rise buildings, a depressing lack of trees and green park space, people walking around without jackets in early December: I'd spent the trip feeling out of sorts and cut off from my usual sense of place. Now, I sat anxiously in the claustrophobic cabin of the plane, preparing for the flight back to Pittsburgh and worrying that I was in for another nauseating, jolting ride.

Susan Greenwood's latest book, The Anthropology of Magic

The central tenet that Greenwood puts forth early in her introductory chapter, and returns to often throughout the text, is that magic is not so much something you do as it is a kind of consciousness. More specifically, magical consciousness is one of participation. For much of the book, in fact, Greenwood's discussion focuses on mapping out the more widely-accepted theories of magic found within the anthropological community, and then illustrating how these traditional theories fail to speak to and reflect the essence of magical consciousness. As a social science, the field of anthropology has tended to strive for standards of rational analysis and objective observation that have served the physical sciences well and proven invaluable in collecting reliable data from controlled experiments. This approach has led many anthropologists to view magic itself as a kind of "failed science," an attempt made in ignorance to control and manipulate the forces of nature, acting on false premises about patterns of relationship and causality. Many anthropologists have therefore concluded that magic is the antithesis of religion, being more concerned with manipulative power than with worship, while at the same time it is merely the embarrassing progenitor of "real" science, with no more to teach and nothing of relevance to contribute to the "civilized" epistemology of more enlightened modern times.. Other theorists, such as Evans-Pritchard, have argued that while belief in magic may be ignorant, it is not "primitive" or inherently irrational; far from it, such social groups as the Azande function with belief systems that are perfectly rational and internally consistent, albeit founded on a few basic wrong assumptions.

The central tenet that Greenwood puts forth early in her introductory chapter, and returns to often throughout the text, is that magic is not so much something you do as it is a kind of consciousness. More specifically, magical consciousness is one of participation. For much of the book, in fact, Greenwood's discussion focuses on mapping out the more widely-accepted theories of magic found within the anthropological community, and then illustrating how these traditional theories fail to speak to and reflect the essence of magical consciousness. As a social science, the field of anthropology has tended to strive for standards of rational analysis and objective observation that have served the physical sciences well and proven invaluable in collecting reliable data from controlled experiments. This approach has led many anthropologists to view magic itself as a kind of "failed science," an attempt made in ignorance to control and manipulate the forces of nature, acting on false premises about patterns of relationship and causality. Many anthropologists have therefore concluded that magic is the antithesis of religion, being more concerned with manipulative power than with worship, while at the same time it is merely the embarrassing progenitor of "real" science, with no more to teach and nothing of relevance to contribute to the "civilized" epistemology of more enlightened modern times.. Other theorists, such as Evans-Pritchard, have argued that while belief in magic may be ignorant, it is not "primitive" or inherently irrational; far from it, such social groups as the Azande function with belief systems that are perfectly rational and internally consistent, albeit founded on a few basic wrong assumptions.What all of these theorists hold in common, Greenwood argues, is their own fundamental bias towards the objective-rational approach of modern Western science, which renders certain key aspects of magic and magical consciousness practically invisible to study and consideration. Yet the human mind and the socio-cultural community function together in ways that are often subjective, nonrational and mythological in nature. Understanding the role that magic plays for individuals and their communities requires an appreciation of these aspects of human experience that cannot easily be reduced to rational analysis or dismissed as psychological quirks. Rather than relying solely on the model of objective experimentation and data collection exemplified in the physical sciences, Greenwood suggests that anthropologists hoping to gain insight into the workings of magical consciousness must be willing to approach the processes of magic on its own terms, and to develop epistemological models that can integrate diverse kinds of rational and nonrational, objective and subjective kinds of knowledge in ways that inform and lend perspective to both. Greenwood herself lives up to this rather intimidating demand for a new generation of anthropologists. Her eloquent accounts of her own participation in magical and shamanic rituals as part of her participatory field research are arguably some of the most engaging and intriguing parts of the text, and they serve as indispensable illustrations of theoretical concepts that might otherwise be too abstract for the reader to fully grasp.

As a result of her participatory approach to research, Greenwood has clearly come to appreciate certain aspects of magic and its role in society that many anthropologists have until now largely overlooked. Picking up an old debate between the two anthropologists, Lévy-Bruhl and Evans-Pritchard, she revisits the possibility that magic is indeed a kind of consciousness distinct from that of logos-based reason so celebrated in the West. At the time Lévy-Bruhl proposed such an argument, his theory was considered implicitly racist, demeaning those of "primitive" cultures as "pre-logical" and lacking the reasoning faculties of more civilized peoples; in response to this misunderstanding of his idea, Evans-Pritchard took on the task of proving that such peoples as the Azande were fully rational and intelligent human beings who were not somehow lesser than their Western counterparts, but merely different. An on-going correspondence between the two researchers continued to inform and clarify Lévy-Bruhl's original theory, however, and Greenwood returns to his suggestion that magical consciousness is, though not degenerate, certainly a unique kind of consciousness distinct from and not reducible to reason alone. (Indeed, as her discussion of the experiment in which sugar-water was labeled "poison" illustrates, modern Western academics themselves are not immune to "magical consciousness" even when their rational minds insist otherwise.)

What characterizes magical consciousness, according to Greenwood's revised hypothesis, is a particular kind of participatory awareness. While traditional Western science relies on analogical reasoning in which participation is characterized by repeatable, controllable outcomes of physical reactions in order to predict similar future results, the analogical participation of magical consciousness is subjective and experiential, informed by culturally-shared myths and shaped by a sense of nonphysical interconnection between objects or events that share metaphorical relationships. In traditional anthropological terms, this describes "sympathetic" and "contagion" magical practices, in which the similarity of ritual acts and objects are seen as in meaningful relationship with those things they symbolize and/or imitate, and objects or people once in contact are understood as maintaining a connection or relationship that can be used to exert influence at a distance. In Greenwood's understanding, however, the basis for sympathetic and contagion magic is not merely inaccurate assumptions about how the physical world functions. Instead, she proposes that these conceived patterns of relationship accurately reflect the subjective experiences of the participants in magical work. They are therefore not only valuable and valid in understanding how and why people utilize magic, but they can actually provide us with meaningful knowledge about the world, insofar as they offer us insight into the perceptions and relationships of the world as we experience it, that the normal consciousness of rational analysis cannot always discover.

Pagans and other modern magical practitioners in the West may find in Greenwood's theory of participatory magical consciousness echoes of some popular definitions of magic among our own communities. One of the most well-known, attributed to Dion Fortune, is that "magic is the art of changing consciousness at will." The various ritual acts described in classic anthropological texts, as well as in Greenwood's own field research, are interpreted in her theory as the means by which individuals and social groups intentionally induce this particular altered state of "magical consciousness" that renders the participant receptive to and capable of perceiving patterns of relationship and participation that are nonrational and emotional (rather than objective and analytical) in nature.

The modern Pagan approach to magical work, with its emphasis on meditation and creative visualization, is very much in keeping with this interpretation. However, in my own experience, the typical Pagan is just as prone to the mistakes of an ingrained rational-scientific bias as the average anthropologists, and this is why Greenwood's work is worthy of study and contemplation not only by those entering the academic world, but for anyone who takes his or her magical work seriously as an integrated part of a larger, authentic spiritual life. Too often, Pagans slip into the habit of mind that approaches magic as merely an occult (i.e. hidden) alternative to mainstream science, with its focus primarily on controlling the forces and energies of nature for particular ends. As I leafed through my pages of notes jostling in my lap, trying to concentrate despite the thrumming engines of the plane as it prepared for take-off, I realized that this was exactly the mistake I had made myself.

As a practicing Druid, I had of course tried a few tricks to help myself adjust to the disorientation of flying. On the trip south to Charlotte, these techniques had proved beyond useless. I experimented with breathing techniques meant to induce relaxation; the result was an overpowering awareness of the pressurized and recirculated air of the cabin. I tried to remain grounded and centered, sensing the edges of my physical body and energetic field, imagining a smooth stone resting in my center as a firm point of stability and connection with the land below; yet the stone turned over and seemed to slosh in my stomach as my small, dense body rattled in my narrow seat with every wave of turbulence or dip of a wing. Magic, it seemed, had failed me.

As a practicing Druid, I had of course tried a few tricks to help myself adjust to the disorientation of flying. On the trip south to Charlotte, these techniques had proved beyond useless. I experimented with breathing techniques meant to induce relaxation; the result was an overpowering awareness of the pressurized and recirculated air of the cabin. I tried to remain grounded and centered, sensing the edges of my physical body and energetic field, imagining a smooth stone resting in my center as a firm point of stability and connection with the land below; yet the stone turned over and seemed to slosh in my stomach as my small, dense body rattled in my narrow seat with every wave of turbulence or dip of a wing. Magic, it seemed, had failed me.But now, with anxiety slowly tightening its grip in my chest, I recalled what Greenwood had written about participation as the key to magical consciousness. She spoke of the unexpected relationships she'd experienced between far distant memories and the sensations of her immediate landscape, and of the tensions of myth and metaphor that drew these disparate events into patterns of meaning and beauty that wove an experience of interconnection with the world. This was magic, after all. I thought back to that first evening in the hotel room, remembering the time I had spent returning to myself and slowly ridding my body of airsickness. The night had been stormy, and outside my window the rain danced in expanding, overlapping ripples that reflected the fluorescent lights of the city in ever-changing patterns as the water beat out a subtle yet complicated soft-shoe rhythm on the roofs above and the pavement far below; I had sat watching and listening, and singing my Awen, the Druidic meditative chant similar to the "Aum" of Hindu practice, until the vibration of breath in my body had released every twinge of tension.

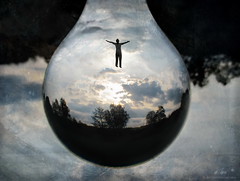

Remembering this experience now, I squared my feet on the floor beneath the seat in front of me and did my best to sit upright and relaxed in the uncomfortable airplane. As the plane roared into movement, raging down the runway and lifting off from the ground, I closed my eyes and sang to myself, letting my Awen expand and fill my awareness. This time, I didn't resist the experience of flight as I had before, I didn't imagine stones or hard boundaries, I didn't try to control the experience and the energies rushing through me. Instead, I allowed the chant to open my body up to vibration, and as I did so I found that my physical body began to vibrate with the thrumming turbulence of the plane. In sympathetic movement, suddenly I could feel the exhilaration of flight not as something wrenching and disorienting, but as comfortable and natural: I was participating in flight with the huge machine around me.

And this experience of participation and interconnection with the world around us is perhaps the most important aspect of Greenwood's theory, though she does not address it explicitly in her text. By understanding magic as a kind of consciousness that places participation at its center, we no longer relegate magic to the realm of anti-religious power-mongering and manipulation. Instead, magical work can open us to a reverence for and enchantment with the world that plays a vital role in an earth-centered spirituality that seeks the sacred in the natural forces and landscapes in which we live our everyday lives. Because of this heightened sense of participation, my experience of the flight north was smooth and almost pleasant, and our descent into the shimmering City of Steel just as the sun was blazing brilliantly in shades of orange and purple on the western horizon infused the journey home with a sense of breathless enchantment I will remember for a long time to come.

Note: This review originally appeared in Sky Earth Sea: A Journal of Practical Spirituality, Spring 2010.

That was really, really fascinating. And now I have another book on my list of "to-reads."

ReplyDeleteI appreciate your writing so much.

This is beautiful Ali, thank you for posting.

ReplyDeleteWhat a wonderful experiential understanding of the book.

ReplyDeleteSusan! So glad you enjoyed it! I wasn't sure if the original review (in SES back in the spring) ever made it back around to you, so I'm glad you had the chance to read it here. :)

ReplyDelete